At only 43, Ryan Marks has already been president of Uesco Cranes for more than five years. During that time, he has led the long-established family company widely regarded as one of the leaders in its field through a process of modernisation that he hopes will maintain its legacy far beyond his tenure in the top job.

The company was founded back in 1921 on the south side of Chicago by Fred Marks, who had been working as an armature winder at General Electric, repairing broken electric motors and rewinding coils before he bought a motor repair and rewind company named Universal Electric Repair Works. Since the beginning, it was its strength as a family business that kept the company running through the Great Depression and, ultimately, saw it move into the overhead crane business.

Through the late 1940s the company’s business interests began to expand and Universal Electric Service – which ultimately became Uesco in the 1970s – expanded beyond commercial electric repair work and motor rewinds to become a distributor of parts in the Great Lakes area and, eventually, a highly respected name in crane manufacturing and service. By the 1980s, it had grown from a local Chicago company to a regional crane builder, and from there it set about expanding its distribution network across the country.

Since Marks took over from his father at the head of the company, it has expanded that network to include 50 distributors across the country, much of that growth coming under his stewardship. But while this may sound like a well-worn road of a family business being handed down seamlessly from one generation to the next, it is not how he had originally seen his life going.

“When I was growing up I imagined being an attorney, but I did a lot of other things along the way,” says Marks. “I was a wedding DJ for ten years and I was a bartender in college while I was studying for one of the two degrees I started, neither of which meant anything at the end of the day.”

An accidental leader

Marks is the fourth generation of his family to be involved in the business, but despite his love for sales – combined with a natural talent – he was not the one initially destined to take the reins.

“I went to school and was going to go into public law, and my brother was supposed to go into the family business, but he has a knack of not making things go the way they should,” he explains. “It wasn’t until I got accepted into law school that my dad, at the age of 85, told me that if I didn’t go into the business he was going to sell it.”

“I knew a lot of the people working in the company and their kids,” he adds. “We all knew their families and we helped provide for them, and they had become part of the company’s long history, its heritage, and we knew that if we sold it then some of those breadwinners would have to find new jobs. It really pulled on the heartstrings. So, it was a personal choice for me, as well as a professional thing.”

His first job was in packaged goods sales, where he was responsible for the equipment that the company did not manufacture, but provided on a resale basis. Selling hoists and jibs to clients in the Illinois market might seem like a great fit for a natural salesman, and Marks certainly saw success quickly. In just over 18 months, he grew the value of that team’s annual sales from almost nothing to more than $1.5m.

So, surely he must have felt right at home? Not at all. “At first I could not stand it,” he remarks. “I knew nothing about the business.”

Marks, however, is not the kind of person who is put off by a challenge. Rather than bluff his way through the job, he instead enrolled in community college to learn the kind of skills that lie at the heart of the company. He learnt AutoCAD, welding and many more manual skills.

“I had never worked with my hands,” he says. “I had been a salesman from my first job as a teenager, which was selling subscriptions to newspapers. I had to learn mechanical things so that I could know what we do, especially if I was going to run the company one day. I never wanted to be someone who had to take people’s word for what they have done – I need to understand it.”

Climbing the corporate ladder

Having transformed the performance of the packaged goods department and developed his own skill set, Marks was looking for other parts of the business that might benefit from a fresh pair of eyes. The parts department stood out as a business unit ripe for change, but his success in revamping it came at a cost.

“That next rung on the ladder was a big mistake,” he says. “We were coming into 2008, when things were going badly for the economy. I made a lot of changes and some were good, but it was not the right place for me. Managing a couple of people and trying to turn order-takers into people who would go out and get business, that was not really my strength. It worked in some ways, but it was very stressful.”

Soon, he moved on to become a regional sales manager responsible for five states in the eastern territory – Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Tennessee and Kentucky – working with a dozen or so of the company’s distributors. Once again, he had a dramatic impact on the team. In four years, he grew its annual turnover from $1.5m annually to more than $6m and added eight more distributors.

“I upset my future wife because I was gone constantly,” he says. “I was putting 50,000–60,000 miles on a car each year. But I could spot companies that would make good distributors, and we sell everything through distributors.”

That success led to the next step up the ladder – national sales manager. That role had been earmarked for a long-serving salesperson who had frequently posted the highest sales numbers over his 16-year tenure, but skill in sales does not always equate to skill in managing a sales team, so Marks soon took over the national team.

In typical fashion, he quickly set about changing systems and eliminating paper-based processes. The goal was better visibility of sales performance without the burden of extra reporting or reliance on meetings with sales people who, if they are doing a good job, should be left to their own devices. So, salespeople were given a system to electronically update their progress as part of their workflow.

“I could review any deal in a few minutes and get on a call with them if necessary,” Marks says. “It was very efficient, and in my time as national sales manager, we grew the company 35% and added two more people and around 15 more distributors. That is when we started to get into the current situation, where sales are outstripping production. That is what I call a champagne problem.”

The view from the top

After a fast ascent, powered by hard work and innovation, Marks became president of the company just as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold. During that period, business shrank by 20%, but a crisis can be a powerful lens to view both the strengths and weaknesses of a business. Marks took the opportunity to look at key departments – notably the parts and service divisions – to unearth ways to improve their culture and processes.

Since coming out of the pandemic, business has grown exponentially, partly due to those changes in personnel and culture.

“If people don’t get along then they are not meant to be in our organisation, even if they have a great work ethic,” says Marks, who spent the pandemic learning how to handle the company’s accounting processes. “We now have a six-tier training programme for production and service because we could not find experienced people.”

He has implemented skills-based training, with micro-raises that can be earned every six months if employees become proficient in new skills. There are quarterly reviews based on what people have learned and helping people learn new skills is reducing attrition.

“Learning skills makes employees sticky – they know they will get some value back from learning skills and that has helped our growth in service and production,” he adds.

His aim was to make the company’s culture suit the modern era, and get people embedded in the business. That approach is working very effectively, as Marks can identify the people who really want to move up in the organisation and reward them appropriately.

“If something had happened to my father or grandfather, the company would not exist,” he says. “So, I’ve spent five years putting people in place to handle the business if I am away to sustain and grow the company.”

Secrets of success

Marks successfully changed his focus from sales to leadership – showing that good leaders can learn to love a business to which they are not naturally drawn and can shape their approach from both the lessons of their predecessors and their own inherent traits.

“I love sales and I did that for a long time,” Marks says. “I know how to do it well, and I rode that roller coaster for years, eating what I killed. Now, I am driven by business growth. So, I’ve had to change. And I’m looking at people retiring and asking who is going to step into those roles. Now, we have back up positions for most senior roles, which allows me to have proper vacations. I just got back from a two-week vacation in Europe, and I have not done that since I got married.”

Coming back from vacation straight into a new project to grow production capacity is no mean feat. Marks is currently working with a real estate developer on a new 70,000ft2 manufacturing facility. He can do so because he has the right people in place. So, he must be a people person, right? Well, not exactly.

“My three children and my wife are my motivation to lead the company, though they would not agree with me,” he explains. “But I am not a very empathetic person, and that can be a problem. I can be very sympathetic and helpful, but my feeling is that if you are at work you are here to do a job and do it right. If you don’t want to be here, you can leave and I’ll find someone else. Work is work, home is home.”

“But for the people who work with and for us, and who care about where the company is going, I want them to improve their lives as much as possible,” he adds. “I put my effort into what will improve their lives, and I look at it generationally. My father was my biggest inspiration, but I had to tell him to put on the dad hat at times, and the boss hat at times. There were times when we butted heads, but he taught me a lot and was a huge influence.”

The approach he takes to any problem comes straight from his father, who told Marks to always do his homework. That said, he is careful not to overprepare.

“I wait until I’m 70% sure and then pull the trigger,” he says. “If I wait for 100% certainty, I will miss the boat.”

His approach is defined by rigour and efficiency. Marks is all about creating systems, efficiencies and automating everything. But despite his confessed lack of empathy, there is still great concern for the people in his care. For example, when he first took over the company, it had a decent retirement programme, but he noticed a trend where younger people were not putting anything in, choosing to live paycheck to paycheck. So, he changed the system.

Now, 3% of pay goes into safe harbour, and a profit-sharing programme takes another 2–3% of earnings. Then a cash balance gives employees a further 2–3%. So, before they choose to put anything aside for retirement, the company has already put in 6–8%.

“I am very system-oriented and I believe in the power of follow-up,” Marks says. “I have never failed to follow up on something, and I will invest in anything that lets me automate and get knowledge out of my brain into a system.

“I have modernised our approach a lot, not least in manufacturing, sales and accounting, and I did it with my own workflows. Since I have taken over, there has been a lot of change and I have pushed people. There has been some attrition because people like to stick with things that are familiar even if they are inefficient, but we can see our production schedules more clearly, and we are big on lean manufacturing now.”

Fit for the future

As well as making internal changes to ensure the company runs more efficiently, Marks has had to deal with a changing business environment affected by competitive pressures and macroeconomic factors.

So far, US tariffs and talks of a trade war have not really hit the industry, and Marks notes that European suppliers have largely taken such matters in their stride. He also foresees some solid growth in the US market ahead, and a generally positive economic environment. The Trump administration’s policy of encouraging investment in the US is undoubtedly good for manufacturing, though there is uncertainty about the future, and a shortage of labour may force companies to automate more processes.

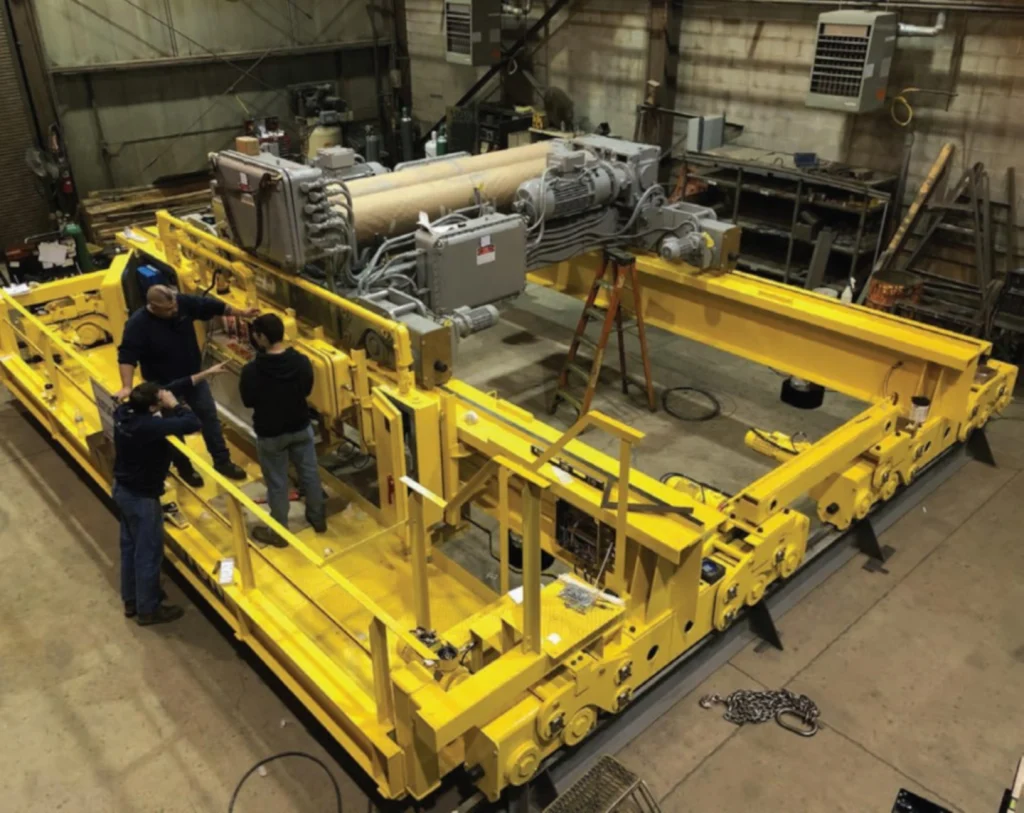

“The automation revolution is here and it will keep growing, so there will be more robots and other automated systems,” he says. “But the industry does not look at crane manufacturing as true manufacturing. It does not see cranes as OEM pieces of equipment. With our size of cranes you have a lot of kit builders using various things other people have built, putting it together and sending it out of the door, so standards have really gone down.”

“I don’t want that to change for the rest of the industry because it allows us to sell more products, and we know how to control our costs,” he adds. “And we are willing to make changes. One recent project was to completely change how we weld, moving away from globular and flux-cored. That sped up our fabrication process by at least 15% and reduced the amount of weld on cranes. So, we see a profit increase. We are raising our own standards. I am a Christian man, so I want the people in the industry to do better and grow, but it is also advantageous for us to grow and improve faster.”

For Marks, staying one step ahead is essential, but while he keeps one eye on the future, he also keeps an eye on the past. Uesco is his family’s heritage, as much as his children are his future.

“I don’t really maintain a work/life balance,” he says. “I often put the interests of the company before my family, but I have a partner who allows me to do it and understands why I do it. In ten years, I hope to get to a point where that changes but for now there is too much I want to get done. We have been around for nearly 105 years and I want to make sure we reach 130 years and beyond.”

Uesco Cranes

One of the largest manufacturers of engineered overhead cranes, gantry cranes and runway systems in the US, Uesco Cranes is a family-owned and operated business founded in 1921. Manufacturing and industrial companies rely on Uesco for daily operations and for the best overhead crane solutions available. Uesco builds both single and double girder cranes in top running and under running configurations with either stationary or rotating axles. With over 100 years in operation and over 50 years of experience building customengineered crane systems, the company has proven that distributors and end users can rely on Uesco to provide a product built to last.